Evergreen Treatment Services (ETS) has been transforming lives and communities through innovative and effective addiction services for five decades. A lot has changed in 50 years. In our “ETS by the Decades” blog series, rather than attempting a full history of substance use treatment and homeless services—topics on which many volumes have been written—we share how select major U.S. events, policies, and public opinions influenced ETS’s services and practices.

For the third part of the series, we review the ways big pharma and the rise of prescription drugs shifted public opinion and interest in substance use, overdose, and addiction. Click on the links to read the first two installments about the 70s and 80s and the 90s. Or skip ahead to learn more about the 2010s.

Donate to ETS to support our life-saving work.

By the turn of the century, Evergreen Treatment Services had provided recovery support services in the Puget Sound region for nearly 30 years. Yet, “treating substance use disorders with medication was not accepted by the mainstream recovery community or society at large…so we kept a low profile,” reflected Dr. Paul Grekin about his early years with the agency in the 1990s. But ETS had always been committed to providing compassionate, evidence-based treatment to support the health and recovery of the community. In fact, in 2001, ETS became a founding Community Partner for the Pacific Northwest node of the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network to improve quality of drug use treatment. This partnership helped ETS provide the highest quality of care to its patients. Still, medication for opioid use disorder remained controversial in the public eye, despite the mounting evidence of its efficacy.

This changed in a big way with the rise of prescription drugs and big pharma that pushed highly addictive opioids into doctor’s offices and pharmacies. The conversations around addiction experienced a noticeable shift in media and public discourse because substance use and overdose now affected white communities whose access to healthcare also provided them more access to prescription drugs. The largest users of prescription drugs in 2007 were white people.

Prescription opioids, like oxycodone, were legally and frequently prescribed for pain throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, though the long-term impacts were uncertain. For instance, prescription opioids were the primary way the military dealt with pain, because they were convinced by drug companies that opioids were safe for long-term treatment of chronic pain. From 2001 to 2009 the number of prescriptions written for pain medication by military physicians more than quadrupled. Nationwide, the dispensing rate of opioid prescriptions in 2006 was 72.4 for every 100 people, peaking in 2012 at 82.1.

These same drugs, though legal, found their way into the illicit drug market on a national scale largely by way of pill mills. Doctors, clinicians, or pharmacies with access to opioids would prescribe or dispense addictive medication to people without knowing their medical history or having documented medical reasons. People would wait in long lines to meet with a doctor or clinician who performed no exams, asked very few questions, and only accepted cash as payment for prescriptions. These “clinics” would often disappear as quickly as they would pop up, making it difficult to shut down the operation for years. But the effects were long-lasting.

At the start of the 2000s, death by overdose with prescription opioids was less than 5,000 nationally. Tragically, deaths by overdose due to prescription opioids nearly tripled by 2010.

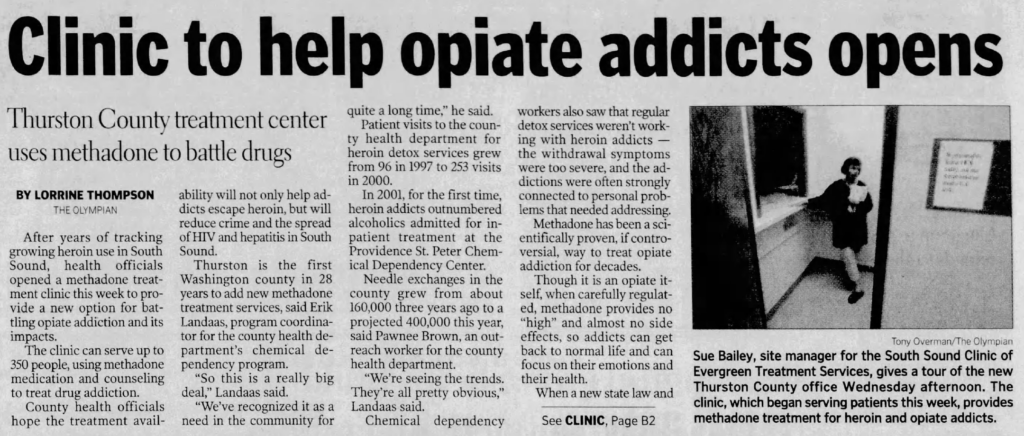

Given the increasing need for recovery support, ETS expanded. In 2002, the South Sound Clinic in Olympia opened and made way for more access to medical care and recovery support. By the end of the 2000s, the agency surpassed 100 staff members and served over 1,500 community members—about three times as much as they had served at the start of the ‘90s. To learn more about major milestones in ETS’s 50-year history, explore the online, interactive timeline.

ETS’s expansion was a response to the needs of the time, but without policy change that supported evidence-based treatment and access to healthcare, it was hard to truly provide the quality and quantity of care the community needed. A major pivot for the organization was the 2010 passing of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which expanded access to Medicaid. Many more clients could now access treatment without artificial caps on how many people the clinic could serve and without staff having to prioritize some patients over others. “Long waiting lists put our staff in a position to make hard decisions about who to accept and who to keep waiting. But the expansion of Medicaid made it so that instead of our team making these tough calls about who was ‘worthy’ of treatment, we could serve more people because they could now access services far more easily,” detailed ETS’s second executive director, Ron Jackson, in his blog.

Though ETS managed to reach more of the community, the opioid epidemic and the devastating loss due to overdose never ended. Stay tuned for the next installment of “ETS by the decades” blog series to understand how the rise of black tar heroin affected drug policy and how ETS showed up for the community in response.