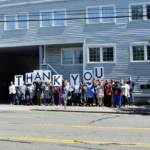

Image description: Brandie Flood (in the left-middle wearing a blue shirt) surrounded by peers at the ETS 50th anniversary celebration.

For fifty years, Evergreen Treatment Services has had the privilege of serving the greater Puget Sound community. Since first opening its doors in 1973, much has changed about ETS. But one thing has remained the same: we put the needs of those we serve first. For ETS, care is evergreen.

Brandie Flood is the director of community justice for our REACH division, having joined our team as a case manager in 2011. For over a decade now, Brandie has shown up with her heart on her sleeve—her approach to harm reduction starts with love. She has progressed the work of Let Everyone Advance with Dignity (LEAD) program and continues to think systemically about community healing.

In the 12 years I’ve been with Evergreen Treatment Services, I’ve learned to never give up on people. There is always more to how people show up if we are willing to go deeper without assuming we understand their story.

I think back to one client I had, Belinda. She was an older Black woman who reminded me of the Black women in my own life who I had lost to drug use. She and I were at the social security office when Belinda had a meltdown. Everyone around us likely assumed she was making a scene for no reason. But in fact, she had encountered someone who was connected to her trauma, and she reacted reasonably to the distress. I was her case manager at the time and the most helpful response was to stay with her.

Struggling with behavioral health issues as a person of color in our city can be dangerous. It’s often seen as a crime, and the response to the behavior is usually violent. It often results in on-lookers, verbal attacks on vulnerable people, and in some cases, a police encounter. We have many vulnerable people who are considered high utilizers of resources due to their unmet behavioral health needs, coupled with drug use and chronic homelessness. I was fortunate to be in a position as a REACH Case Manager to keep offer some level of protection in that moment years ago in the social security office.

Black people are not safe to be raw in their emotions in this country; people tend to assume there is a threat when Black people express themselves. Rather than tend to the onlookers, I focused on Belinda, assuring her that it was okay to feel.

This is what harm reduction is: providing a space where individuals who are struggling to make a change can be respected, treated with dignity, and offered a loving compassionate approach to service delivery. In my case, that has often meant being present with the person, as I did with Belinda. I have to think about my own safety, too. As a Black woman in our society there are not a lot of spaces where I feel safe. This is especially true working in the field with clients who are deemed unworthy of protection as well. I have to be intentional about how, when, and who I access safety from when working with clients in the field.

In most cases, law enforcement response is not necessary and often escalates behavioral health incidents with clients in the field (which puts us both at risk due to issues of racism). It’s important for me to take clinical harm reduction approaches in this work as a means of public safety and support for the individual and the community, making situational awareness key to providing direct service. So, the safest choice is often my first choice, because it protects them and me. That’s how we form trust—the relationships we build with our clients are the most valuable support we offer.

I started at ETS as a case manager in 2011 while completing my master’s in social work, but I was always interested in our community outreach. It was important to me to work with Black people to support their healing and safety and change the systems that continue to cause harm. To do that, I knew I had to be where people are and in the rooms with people who influence those systems.

By the time I completed my master’s, REACH was expanding. I became one of its first supervisors, where I focused a lot of my efforts into the LEAD program. Today, I am the director of community justice.

I see my role as creating the vision for how we operate in the world of diversion. I don’t think there’s anyone in our community that drug use has not touched in some way. LEAD changes the way Seattle law enforcement handles people accused of repeat, low-level drug-related crimes—REACH provides case management and access to services to divert people from incarceration and guide them towards rehabilitation. We believe people deserve care, regardless of their drug use.

But we do not have systems set up to care for the people we serve, and we have experienced resistance to our efforts. Working in substance use treatment, homelessness, and with the criminal-legal system puts us in the position to have to fight to persist, because our clients and staff are often the targets of aggression. When I first started, Ron Jackson was still our executive director, and we were trying to open a methadone clinic in Bremerton. The pushback was fierce. Reading the articles and online comments revealed how much we would have to fight to keep our doors open.

People assume our clients are difficult or harmful when really, it’s the circumstances they are in. Our staff support people experiencing a multitude of oppressive systems—poverty, racism, and insufficient access to effective healthcare. We have to be mindful of how we describe someone’s behavior when trying to get them services. If we ask for extra support from medics, police, or firefighters, how we describe the situation and the state of the person we’re with impacts how they show up and the assistance they’re willing to offer. When you are a harm reduction professional, these are the decisions you’re always making. It is a skill, and it takes compassion.

Often, I hear people call what we do “heart-work.” At ETS, we know recovery is a lifetime commitment, and we know long-term case management and treatment works. So, we have to put our hearts into this work to stand by our clients for as long as they need us. But it’s also hard work.

The murder of George Floyd was the most challenging time I’ve had trying to do my job. My belief in community justice motivates me to be among the people who are doing the most harm to the communities we work with. That means partnering with prosecutors and police to create a plan for someone who may have an arrest warrant but could have housing if we worked together. The relationships we build with community leaders and politicians help us influence legislation, so our social systems serve our community better. I lost friends because of my work throughout 2020; they couldn’t see what I did. I see the power of our work changing systems. Law enforcement now approaches REACH and our partners through LEAD for insights and collaboration, especially on citywide proposals.

We cannot do this alone. Finding solutions is a collaborative effort. That is why I am so adamant about being where the most harm is—we need to be at the table advocating for our clients. Telling policymakers and law enforcement that there is another way, that we can move away from punitive reactions to homelessness and drug use. We have the research and the lived experience to prove we can create and invest in more compassionate, restorative models of care. When we work together to think about the larger systems enabling inequity and collaborate on a plan for implementation, that’s when the healing begins.

Thank you for your compassionate work in this field! Keep up the good work!